As I promised you last time, today I will talk about one of the central data structures that we’ll use throughout the rest of the series, so buckle up and let’s go.

正如我上次所承诺的那样,今天将讨论我们将在本系列的其余部分中使用的核心数据结构之一,所以系好安全带,我们出发吧。

Up until now, we had our interpreter and parser code mixed together and the interpreter would evaluate an expression as soon as the parser recognized a certain language construct like addition, subtraction, multiplication, or division. Such interpreters are called syntax-directed interpreters. They usually make a single pass over the input and are suitable for basic language applications. In order to analyze more complex Pascal programming language constructs, we need to build an intermediate representation (IR). Our parser will be responsible for building an IR and our interpreter will use it to interpret the input represented as the IR.

到目前为止,我们把解释器和解析器代码混合在一起,一旦解析器识别出某种语言结构,比如加、减、乘、除,解释器就会计算一个表达式。这样的解释器被称为语法导向解释器。它们通常只对输入进行一次传递,适用于基本的语言应用程序。为了分析更复杂的 Pascal 编程语言结构,我们需要构建一个中间表示(intermediate representation,IR)。解析器将负责构建一个 IR,然后解释器将使用它来解释 用IR表示的输入。

It turns out that a tree is a very suitable data structure for an IR.

事实证明,树是一种非常适合 IR 的数据结构。

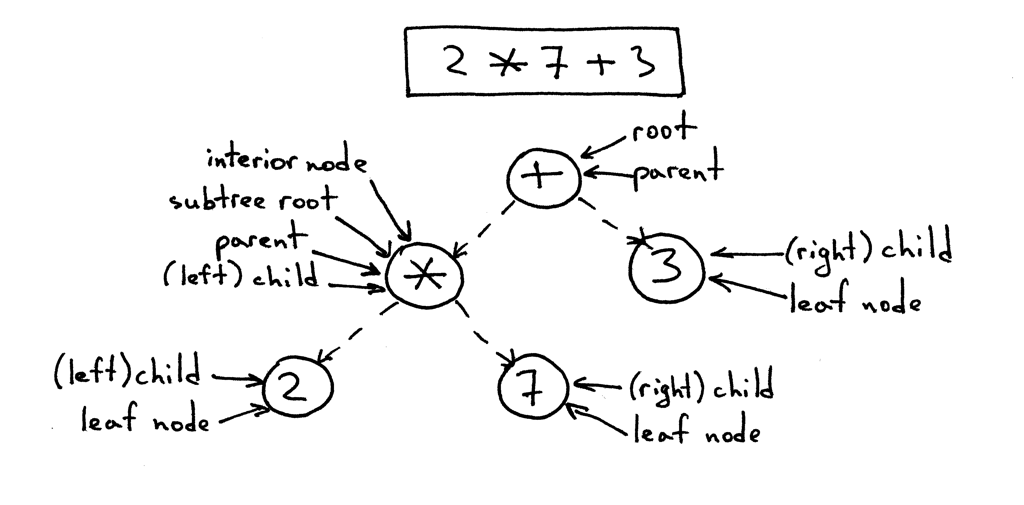

Let’s quickly talk about tree terminology.

让我们快速讨论一下关于树的术语。

- A tree is a data structure that consists of one or more nodes organized into a hierarchy.

- 树是一种数据结构,它由一个或多个节点组织成一个层次结构

- The tree has one root, which is the top node.

- 树有一个顶部节点root

- All nodes except the root have a unique parent.

- 除root以外的所有节点都有一个唯一的父节点

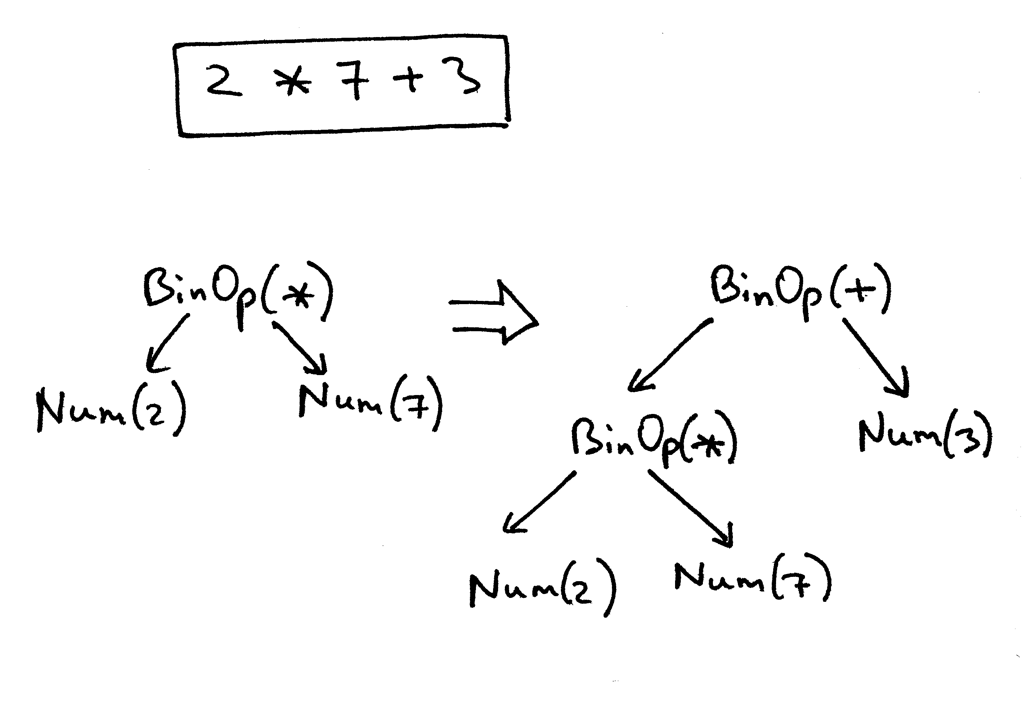

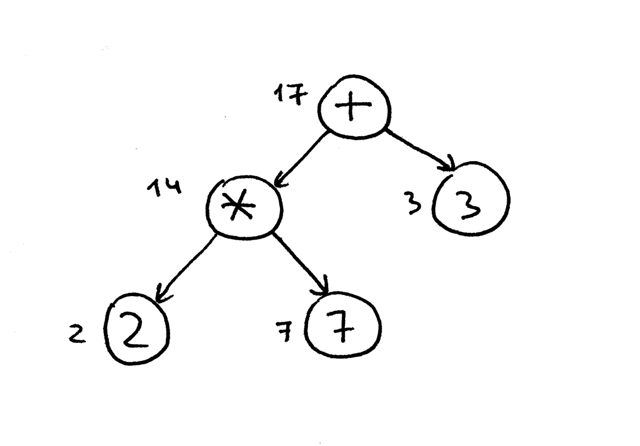

- The node labeled ***** in the picture below is a parent. Nodes labeled 2 and 7 are its children; children are ordered from left to right.

- 下图中标记为*的节点是父节点。标记为2和7的节点是它的子节点;子节点们按从左到右的顺序排列。

- A node with no children is called a leaf node.

- 没有子节点的节点称为叶节点(leaf node)。

- A node that has one or more children and that is not the root is called an interior node.

- 有一个或多个子节点且不是root节点的节点称为内部节点(interior node)。

- The children can also be complete subtrees. In the picture below the left child (labeled *****) of the + node is a complete subtree with its own children.

- 子节点也可以是完整的子树。在下面的图片中,+节点的左子节点(标记为*)是一个完整的子树,它有自己的子节点。

- In computer science we draw trees upside down starting with the root node at the top and branches growing downward.

- 在计算机科学中,我们倒过来画树,从顶部的root节点开始,树枝向下生长。

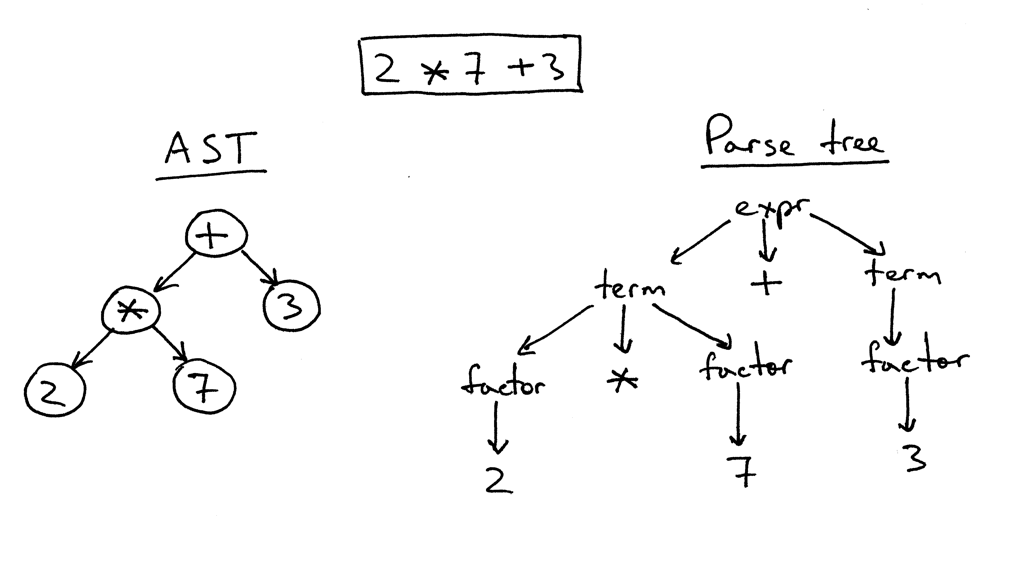

Here is a tree for the expression 2 * 7 + 3 with explanations:

下面是表达式2 * 7 + 3的一棵树,并附有解释:

The IR we’ll use throughout the series is called an abstract-syntax tree (AST). But before we dig deeper into ASTs let’s talk about parse trees briefly. Though we’re not going to use parse trees for our interpreter and compiler, they can help you understand how your parser interpreted the input by visualizing the execution trace of the parser. We’ll also compare them with ASTs to see why ASTs are better suited for intermediate representation than parse trees.

我们将在整个系列中使用的 IR 称为抽象语法树(abstract-syntax tree,AST)。但是在我们更深入地研究 ASTs 之前,让我们先简要地讨论一下解析树(parse trees)。虽然我们不打算为解释器和编译器使用解析树,但是它们可以通过将解析器的执行轨迹可视化来帮助你来理解解析器是如何解释输入的。我们还将把它们与 ASTs 进行比较,看看为什么 AST 比解析树更适合中间表示。

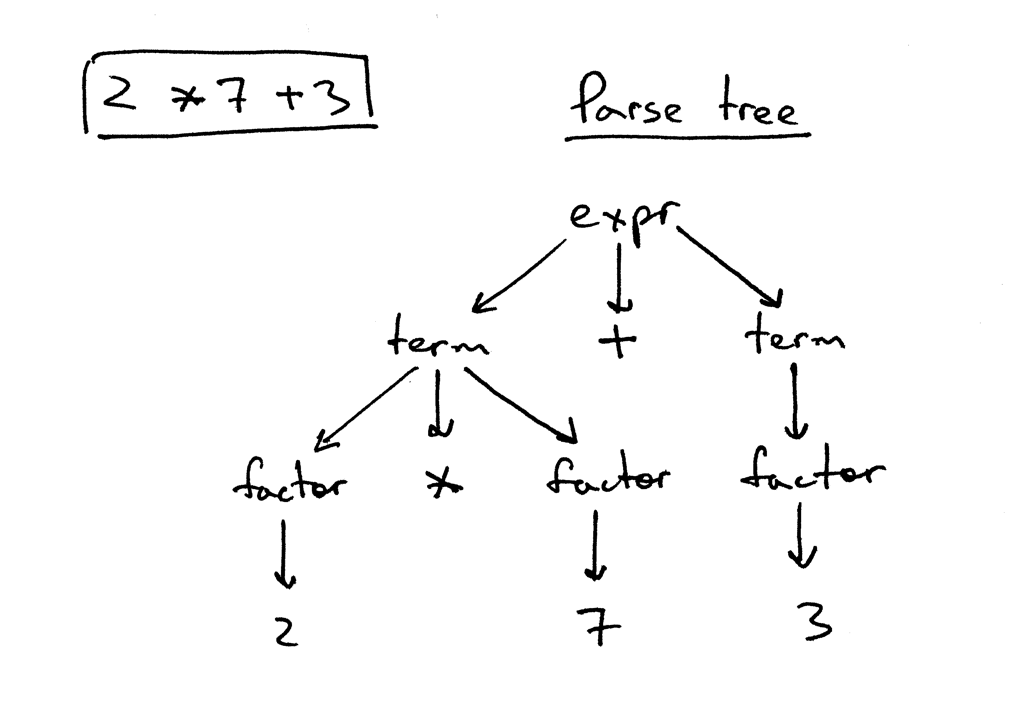

So, what is a parse tree? A parse-tree (sometimes called a concrete syntax tree) is a tree that represents the syntactic structure of a language construct according to our grammar definition. It basically shows how your parser recognized the language construct or, in other words, it shows how the start symbol of your grammar derives a certain string in the programming language.

那么,什么是解析树?解析树(有时称为具体语法树——concrete syntax tree)是一棵树,这棵树根据grammar的定义表示语言结构的句法结构(syntactic structure)。它基本上显示了解析器如何识别语言结构,或者换句话说,它显示了grammar的起始符号如何在编程语言中派生某个字符串。

The call stack of the parser implicitly represents a parse tree and it’s automatically built in memory by your parser as it is trying to recognize a certain language construct.

解析器的调用堆栈隐式地表示一个解析树,当解析器试图识别某种语言结构时,它会自动构建在内存中。

Let’s take a look at a parse tree for the expression 2 * 7 + 3:

让我们看一下表达式2 * 7 + 3的解析树:

In the picture above you can see that:

在上面的图片中你可以看到:

- The parse tree records a sequence of rules the parser applies to recognize the input.

- 解析树记录了解析器用于识别输入的一系列规则

- The root of the parse tree is labeled with the grammar start symbol.

- 解析树的root用grammar起始符号标记

- Each interior node represents a non-terminal, that is it represents a grammar rule application, like _expr _, term, or factor in our case.

- 每个内部节点代表一个非终结符,即它表示一个grammar规则应用,如在我们的例子中是expr、term或者factor。

- Each leaf node represents a token.

- 每个叶节点代表一个token

As I’ve already mentioned, we’re not going to manually construct parser trees and use them for our interpreter but parse trees can help you understand how the parser interpreted the input by visualizing the parser call sequence.

正如我已经提到的,我们不打算手动构造解析树并将它们用于解释器,但解析树可以通过将解析器调用序列可视化来帮助你理解解析器如何解释输入。

You can see how parse trees look like for different arithmetic expressions by trying out a small utility called genptdot.py that I quickly wrote to help you visualize them. To use the utility you first need to install Graphviz package and after you’ve run the following command, you can open the generated image file parsetree.png and see a parse tree for the expression you passed as a command line argument:

通过尝试一个名为 genptdot.py 的小工具程序,你可以看到不同算术表达式的解析树是什么样子的,我快速编写了这个工具程序来帮助你将它们可视化。要使用这个工具,你首先需要安装 Graphviz 包,在你运行下面的命令之后,你可以打开生成的图片文件 parsetree.png,然后看到一个和作为命令行参数传递的表达式对应的解析树于:

$ python genptdot.py "14 + 2 * 3 - 6 / 2" > \

parsetree.dot && dot -Tpng -o parsetree.png parsetree.dot

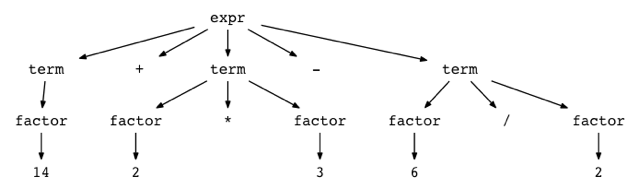

Here is the generated image parsetree.png for the expression 14 + 2 * 3 - 6 / 2:

下面是为表达式14 + 2 * 3-6/2生成的图像 parsetree.png:

Play with the utility a bit by passing it different arithmetic expressions and see what a parse tree looks like for a particular expression.

通过向该工具程序传递不同的算术表达式,了解特定表达式的解析树是什么样的。

Now, let’s talk about abstract-syntax trees (AST). This is the intermediate representation (IR) that we’ll heavily use throughout the rest of the series. It is one of the central data structures for our interpreter and future compiler projects.

现在,让我们讨论一下抽象语法树(AST)。这是中间表示(intermediate representation,IR) ,我们将在本系列的其余部分大量使用它。它是我们的解释器和未来编译器项目的核心数据结构之一。

Let’s start our discussion by taking a look at both the AST and the parse tree for the expression 2 * 7 + 3:

让我们先来看一下表达式2 * 7 + 3的 AST 和解析树:

As you can see from the picture above, the AST captures the essence of the input while being smaller.

正如你从上面的图片中看到的,AST 捕获了输入的本质,同时也变得更小了。

Here are the main differences between ASTs and Parse trees:

以下是 ASTs 和 解析树之间的主要区别:

- ASTs uses operators/operations as root and interior nodes and it uses operands as their children.

- ASTs 使用操作符/操作作为根节点和内部节点,并使用操作数作为它们的子节点

- ASTs do not use interior nodes to represent a grammar rule, unlike the parse tree does.

- 与解析树不同,ASTs不使用内部节点来表示grammar规则

- ASTs don’t represent every detail from the real syntax (that’s why they’re called abstract) - no rule nodes and no parentheses, for example.

- ASTs并不代表真实syntax中的每一个细节(这就是它们被称为抽象的原因)——例如,没有规则节点和括号。

- ASTs are dense compared to a parse tree for the same language construct.

- 与同一语言构造的解析树相比,ASTs是密集的

So, what is an abstract syntax tree? An abstract syntax tree (AST) is a tree that represents the abstract syntactic structure of a language construct where each interior node and the root node represents an operator, and the children of the node represent the operands of that operator.

那么,什么是抽象语法树?抽象语法树是一个树,它表示语言结构的抽象语法结构,其中每个内部节点和根节点代表一个操作符,这些节点的子节点代表该操作符的操作数。

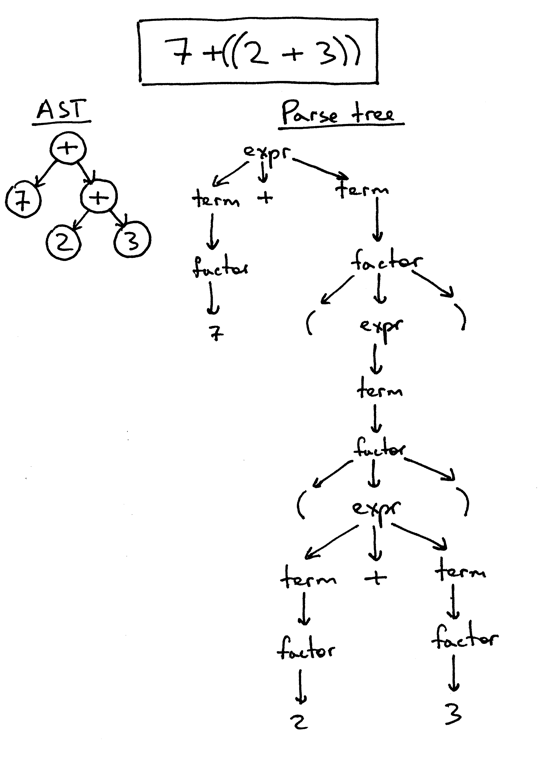

I’ve already mentioned that ASTs are more compact than parse trees. Let’s take a look at an AST and a parse tree for the expression 7 + ((2 + 3)). You can see that the following AST is much smaller than the parse tree, but still captures the essence of the input:

我已经提到,ASTs 比解析树更紧凑。让我们看一下表达式7 + ((2 + 3))的 AST 和解析树。你可以看到下面的 AST 比解析树小得多,但仍然抓住了输入的本质:

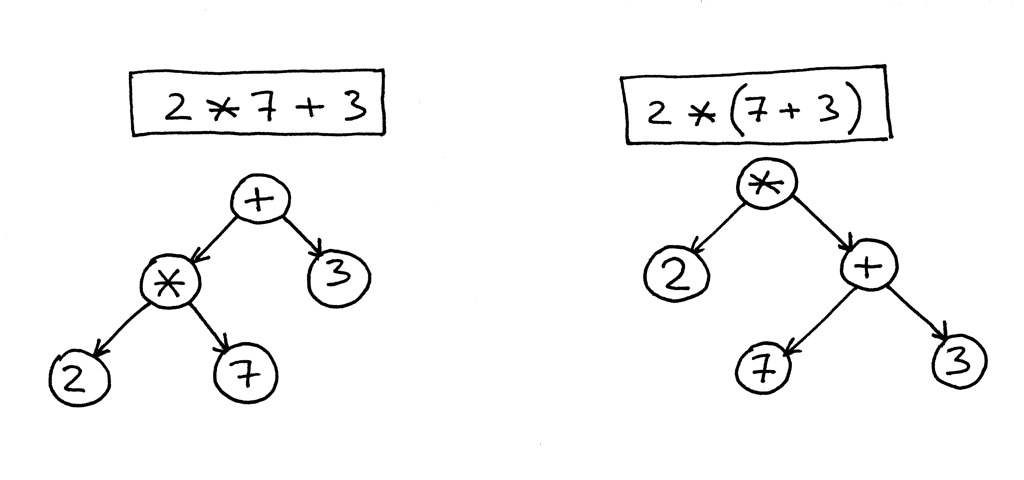

So far so good, but how do you encode operator precedence in an AST? In order to encode the operator precedence in AST, that is, to represent that “X happens before Y” you just need to put X lower in the tree than Y. And you’ve already seen that in the previous pictures.

到目前为止还不错,但是如何在 AST 中编码运算符优先级呢?为了在 AST 中编码运算符的优先级,也就是说,为了表示“ x 先于 y 发生”,你只需要在树中将 x 放在比 y 低的位置,你已经在前面的图片中看到了这一点。

Let’s take a look at some more examples.

让我们来看看更多的例子。

In the picture below, on the left, you can see an AST for the expression 2 * 7 + 3. Let’s change the precedence by putting 7 + 3 inside the parentheses. You can see, on the right, what an AST looks like for the modified expression 2 * (7 + 3):

在下面的图片中,在左边,你可以看到表达式2 * 7 + 3的 AST。让我们把7 + 3放在括号内来改变优先顺序。你可以看到,在右边,AST 对于修改后的表达式2 * (7 + 3)是什么样的:

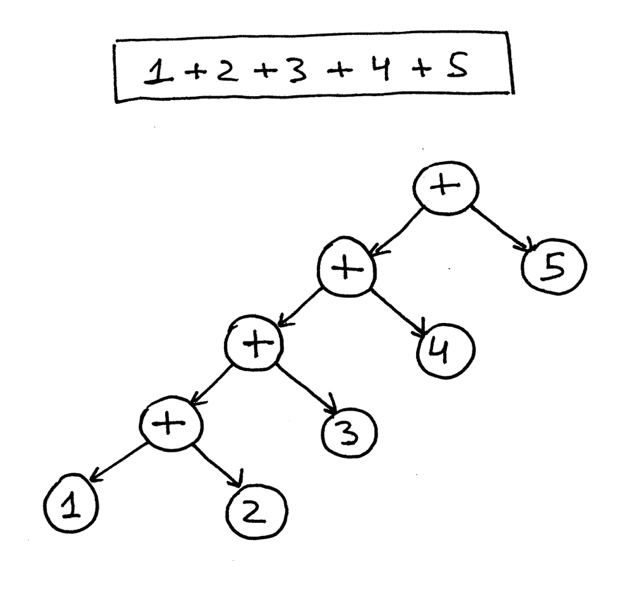

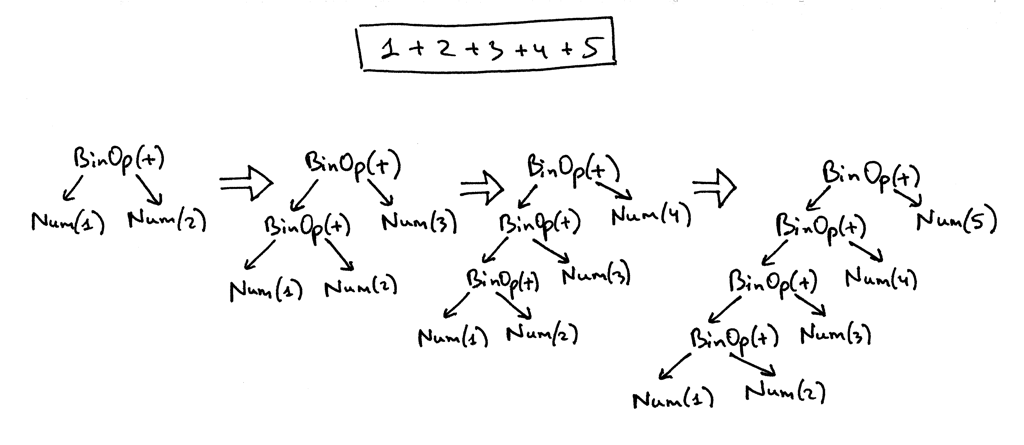

Here is an AST for the expression 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5:

下面是表达式1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5的 AST:

From the pictures above you can see that operators with higher precedence end up being lower in the tree.

从上面的图片中可以看到,优先级较高的操作符最终在树中的位置较低。

Okay, let’s write some code to implement different AST node types and modify our parser to generate an AST tree composed of those nodes.

好的,让我们编写一些代码来实现不同的 AST 节点类型,并修改我们的解析器以生成由这些节点组成的 AST 树。

First, we’ll create a base node class called AST that other classes will inherit from:

首先,我们将创建一个名为 AST 的基本节点类,其他类将从这个类继承:

class AST(object):

pass

Not much there, actually. Recall that ASTs represent the operator-operand model. So far, we have four operators and integer operands. The operators are addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. We could have created a separate class to represent each operator like AddNode, SubNode, MulNode, and DivNode, but instead we’re going to have only one BinOp class to represent all four binary operators (a binary operator is an operator that operates on two operands):

实际上,没有多少。回想一下,AST 表示操作符-操作数模型。到目前为止,我们有四个运算符和整数操作数。运算符是加法、减法、乘法和除法。我们本可以创建一个单独的类来表示每个操作符,比如 AddNode、 SubNode、 MulNode 和 DivNode,但是我们决定只写一个 BinOp 类来表示所有四个二元操作符(二元操作符是对两个操作数进行操作的操作符):

class BinOp(AST):

def __init__(self, left, op, right):

self.left = left

self.token = self.op = op

self.right = right

The parameters to the constructor are left, op, and right, where left and right point correspondingly to the node of the left operand and to the node of the right operand. Op holds a token for the operator itself: Token(PLUS, ‘+’) for the plus operator, Token(MINUS, ‘-‘) for the minus operator, and so on.

构造函数的参数是left、 op 和right,其中left和right相应地指向左操作数的节点和右操作数的节点。Op 为运算符本身保存一个token:加号运算符的token(PLUS,‘ +’) ,减号运算符的token(MINUS,‘-’) ,等等。

To represent integers in our AST, we’ll define a class Num that will hold an INTEGER token and the token’s value:

为了在 AST 中表示整数,我们将定义一个类 Num,它将包含一个 INTEGER token和该token的值:

class Num(AST):

def __init__(self, token):

self.token = token

self.value = token.value

As you’ve noticed, all nodes store the token used to create the node. This is mostly for convenience and it will come in handy in the future.

正如你所注意到的,所有节点都存储了用于创建节点的token(self.token)。这主要是为了方便,将来会派上用场。

Recall the AST for the expression 2 * 7 + 3. We’re going to manually create it in code for that expression:

回想表达式2 * 7 + 3的 AST。我们将用代码手动创建这个表达式:

>>> from spi import Token, MUL, PLUS, INTEGER, Num, BinOp

>>>

>>> mul_token = Token(MUL, '*')

>>> plus_token = Token(PLUS, '+')

>>> mul_node = BinOp(

... left=Num(Token(INTEGER, 2)),

... op=mul_token,

... right=Num(Token(INTEGER, 7))

... )

>>> add_node = BinOp(

... left=mul_node,

... op=plus_token,

... right=Num(Token(INTEGER, 3))

... )

Here is how an AST will look with our new node classes defined. The picture below also follows the manual construction process above:

下图展示了定义了新的Node类后 AST 的样子。下图仍遵循上述人工建造过程:

Here is our modified parser code that builds and returns an AST as a result of recognizing the input (an arithmetic expression):

下面是我们修改后的解析器代码,它在识别输入(算术表达式)后构建并返回 AST:

class AST(object):

pass

class BinOp(AST):

def __init__(self, left, op, right):

self.left = left

self.token = self.op = op

self.right = right

class Num(AST):

def __init__(self, token):

self.token = token

self.value = token.value

class Parser(object):

def __init__(self, lexer):

self.lexer = lexer

# set current token to the first token taken from the input

self.current_token = self.lexer.get_next_token()

def error(self):

raise Exception('Invalid syntax')

def eat(self, token_type):

# compare the current token type with the passed token

# type and if they match then "eat" the current token

# and assign the next token to the self.current_token,

# otherwise raise an exception.

if self.current_token.type == token_type:

self.current_token = self.lexer.get_next_token()

else:

self.error()

# 返回的是Num类对象

def factor(self):

"""factor : INTEGER | LPAREN expr RPAREN"""

token = self.current_token

if token.type == INTEGER:

self.eat(INTEGER)

return Num(token)

elif token.type == LPAREN:

self.eat(LPAREN)

node = self.expr()

self.eat(RPAREN)

return node

# 返回的是BinOp对象

def term(self):

"""term : factor ((MUL | DIV) factor)*"""

node = self.factor()

while self.current_token.type in (MUL, DIV):

token = self.current_token

if token.type == MUL:

self.eat(MUL)

elif token.type == DIV:

self.eat(DIV)

node = BinOp(left=node, op=token, right=self.factor())

return node

def expr(self):

"""

expr : term ((PLUS | MINUS) term)*

term : factor ((MUL | DIV) factor)*

factor : INTEGER | LPAREN expr RPAREN

"""

node = self.term()

while self.current_token.type in (PLUS, MINUS):

token = self.current_token

if token.type == PLUS:

self.eat(PLUS)

elif token.type == MINUS:

self.eat(MINUS)

node = BinOp(left=node, op=token, right=self.term())

return node

def parse(self):

return self.expr()

Let’s go over the process of an AST construction for some arithmetic expressions.

让我们回顾一下一些算术表达式的 AST 构造过程。

If you look at the parser code above you can see that the way it builds nodes of an AST is that each BinOp node adopts the current value of the node variable as its left child and the result of a call to a term or factor as its right child, so it’s effectively pushing down nodes to the left and the tree for the expression 1 +2 + 3 + 4 + 5 below is a good example of that. Here is a visual representation how the parser gradually builds an AST for the expression 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5:

如果你看看上面的解析器代码,你会发现它构建 AST 节点的方式是,每个 BinOp 节点采用node变量的当前值作为它的左子节点,调用一个term或factor的结果作为它的右子节点,所以它有效地将节点向左下推,下面表达式1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5的树就是一个很好的例子。下面是解析器如何为表达式1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5逐步构建 AST 的可视化表示:

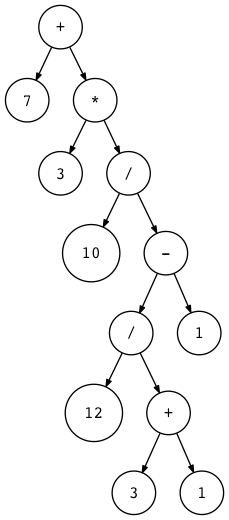

To help you visualize ASTs for different arithmetic expressions, I wrote a small utility that takes an arithmetic expression as its first argument and generates a DOT file that is then processed by the dot utility to actually draw an AST for you (dot is part of the Graphviz package that you need to install to run the dot command). Here is a command and a generated AST image for the expression 7 + 3 * (10 / (12 / (3 + 1) - 1)):

为了帮助你可视化不同算术表达式的 AST,我编写了一个小功能程序,它将算术表达式作为第一个参数,并生成一个 dot 文件,然后由 dot 功能程序处理该文件,以便实际为您绘制 AST (dot是Graphviz 包的一部分,需要安装它以运行 dot 命令 )。下面是表达式7 + 3 * (10/(12/(3 + 1)-1))的命令和生成的 AST 图:

$ python genastdot.py "7 + 3 * (10 / (12 / (3 + 1) - 1))" > \

ast.dot && dot -Tpng -o ast.png ast.dot

It’s worth your while to write some arithmetic expressions, manually draw ASTs for the expressions, and then verify them by generating AST images for the same expressions with the genastdot.py tool. That will help you better understand how ASTs are constructed by the parser for different arithmetic expressions.

编写一些算术表达式是值得的,手动为表达式绘制 AST,然后使用 genastdot.py 工具为相同的表达式生成 AST 图像来验证它们。这将帮助您更好地理解解析器如何为不同的算术表达式构造 ast。

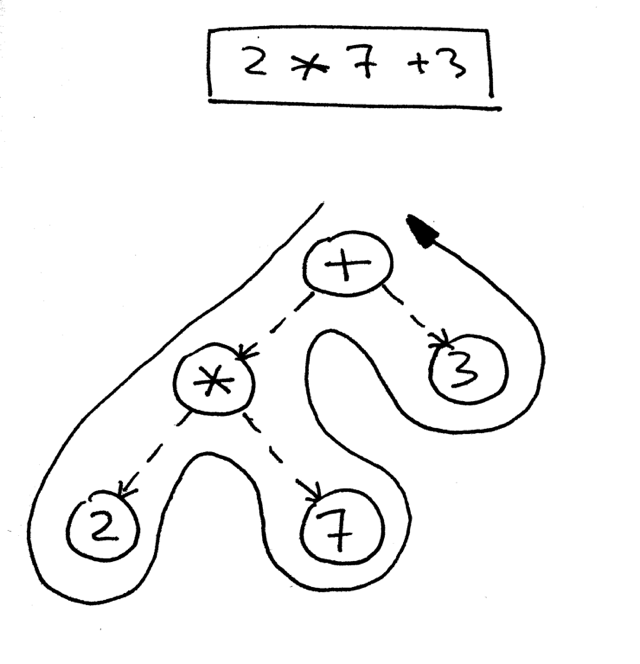

Okay, here is an AST for the expression 2 * 7 + 3:

好的,这是表达式2 * 7 + 3的 AST:

How do you navigate the tree to properly evaluate the expression represented by that tree? You do that by using a postorder traversal - a special case of depth-first traversal - which starts at the root node and recursively visits the children of each node from left to right. The postorder traversal visits nodes as far away from the root as fast as it can.

如何在树中导航以正确计算该树表示的表达式?您可以通过使用后序遍历(一种深度优先遍历的特殊情况)来实现这一点,该遍历从根节点开始,并从左到右递归地遍历每个节点的子节点。后序遍历尽可能快地访问远离根的节点。

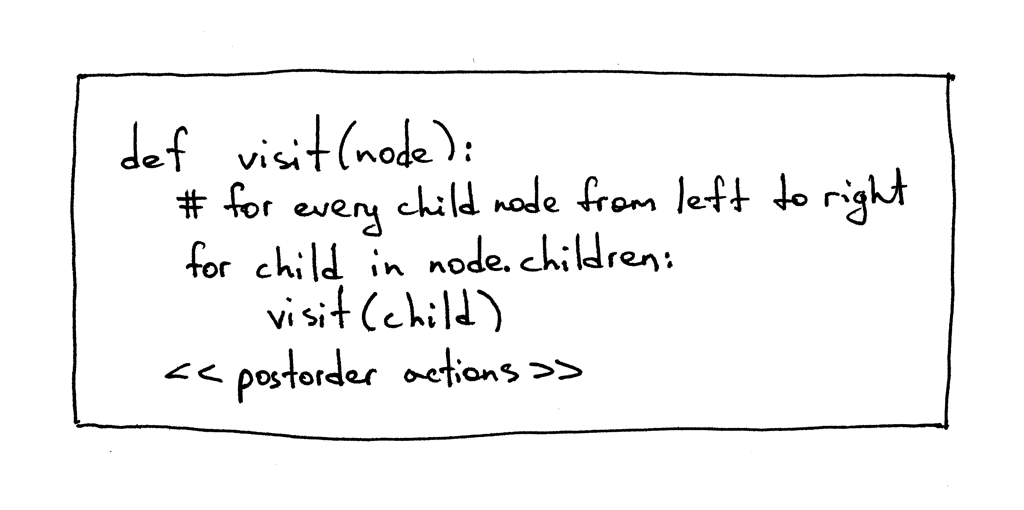

Here is a pseudo code for the postorder traversal where <> is a placeholder for actions like addition, subtraction, multiplication, or division for a BinOp node or a simpler action like returning the integer value of a Num node:

下面是后序遍历的伪代码,其中 < > 是一个占位符,用于对 BinOp 节点进行加法、减法、乘法或除法操作,或者一个更简单的操作,如返回 Num 节点的整数值:

The reason we’re going to use a postorder traversal for our interpreter is that first, we need to evaluate interior nodes lower in the tree because they represent operators with higher precedence and second, we need to evaluate operands of an operator before applying the operator to those operands. In the picture below, you can see that with postorder traversal we first evaluate the expression 2 * 7 and only after that we evaluate 14 + 3, which gives us the correct result, 17:

我们使用后序遍历解释器的原因是,首先,我们需要计算树中较低的内部节点,因为它们表示具有较高优先级的运算符; 其次,我们需要计算运算符的操作数,然后再将运算符应用于这些操作数。在下面的图片中,你可以看到,通过后序遍历,我们首先计算表达式2 * 7,然后计算14 + 3,得到了正确的结果17:

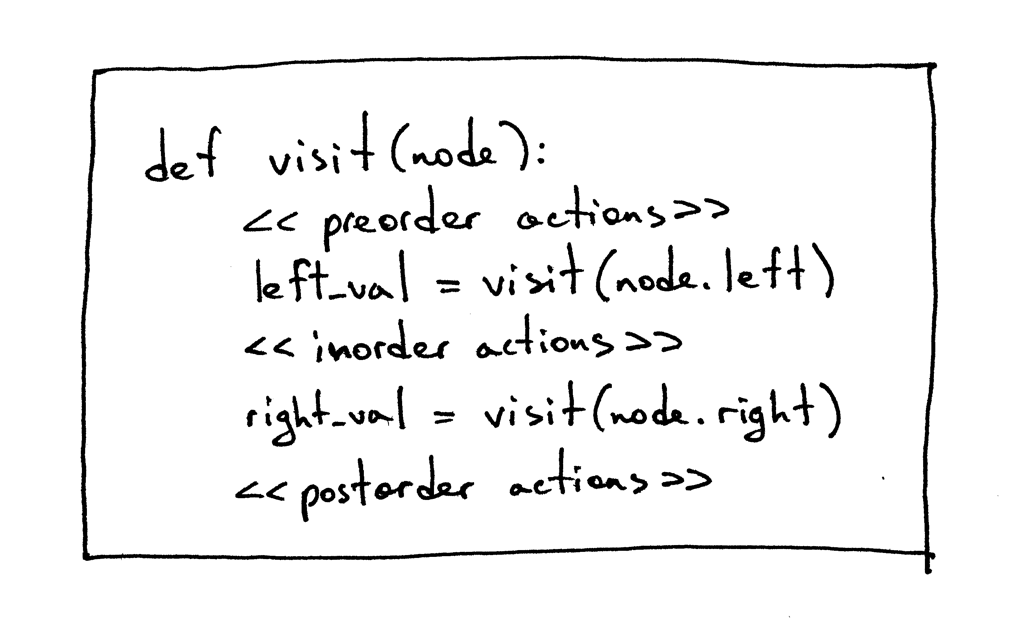

For the sake of completeness, I’ll mention that there are three types of depth-first traversal: preorder traversal, inorder traversal, and postorder traversal. The name of the traversal method comes from the place where you put actions in the visitation code:

为了完整起见,我将提到深度优先遍历有三种类型: 前序遍历、中序遍历和后序遍历。遍历方法的名称来源于访问代码中的操作:

Sometimes you might have to execute certain actions at all those points (preorder, inorder, and postorder). You’ll see some examples of that in the source code repository for this article.

有时候,您可能必须在所有这些点上执行某些操作(前序遍历、中序遍历和后序遍历)。你可以在本文的源代码仓库中看到一些这方面的例子。

Okay, let’s write some code to visit and interpret the abstract syntax trees built by our parser, shall we?

好的,让我们编写一些代码来访问和解释解析器构建的抽象语法树,好吗?

Here is the source code that implements the Visitor pattern:

下面是实现Visitor pattern的源代码:

class NodeVisitor(object):

def visit(self, node):

method_name = 'visit_' + type(node).__name__

visitor = getattr(self, method_name, self.generic_visit)

return visitor(node)

def generic_visit(self, node):

raise Exception('No visit_{} method'.format(type(node).__name__))

And here is the source code of our Interpreter class that inherits from the NodeVisitor class and implements different methods that have the form visit_NodeType, where NodeType is replaced with the node’s class name like BinOp, Num and so on:

下面是我们的 Interpreter 类的源代码,它继承了 _NodeVisitor _类,实现了不同的方法,具有 visit_NodeType 的形式,其中 NodeType 被节点的类名所替换,比如 BinOp、 Num 等:

class Interpreter(NodeVisitor):

def __init__(self, parser):

self.parser = parser

def visit_BinOp(self, node):

if node.op.type == PLUS:

return self.visit(node.left) + self.visit(node.right)

elif node.op.type == MINUS:

return self.visit(node.left) - self.visit(node.right)

elif node.op.type == MUL:

return self.visit(node.left) * self.visit(node.right)

elif node.op.type == DIV:

return self.visit(node.left) / self.visit(node.right)

def visit_Num(self, node):

return node.value

There are two interesting things about the code that are worth mentioning here: First, the visitor code that manipulates AST nodes is decoupled from the AST nodes themselves. You can see that none of the AST node classes (BinOp and Num) provide any code to manipulate the data stored in those nodes. That logic is encapsulated in the Interpreter class that implements the NodeVisitor class.

这里值得一提的代码有两个有趣的地方:首先,操作 AST 节点的visitor代码与 AST 节点本身解耦。可以看到,AST 节点类(BinOp 和 Num)都没有提供任何代码来操作存储在这些节点中的数据。该逻辑封装在实现 NodeVisitor 类的 Interpreter 类中。

Second, instead of a giant if statement in the NodeVisitor’s visit method like this:

第二,不要像下面这样用巨大的 if 语句代替 NodeVisitor 的访问方式:

def visit(node):

node_type = type(node).__name__

if node_type == 'BinOp':

return self.visit_BinOp(node)

elif node_type == 'Num':

return self.visit_Num(node)

elif ...

# ...

or like this:

或者像这样:

def visit(node):

if isinstance(node, BinOp):

return self.visit_BinOp(node)

elif isinstance(node, Num):

return self.visit_Num(node)

elif ...

the NodeVisitor’s visit method is very generic and dispatches calls to the appropriate method based on the node type passed to it. As I’ve mentioned before, in order to make use of it, our interpreter inherits from the NodeVisitor class and implements necessary methods. So if the type of a node passed to the visit method is BinOp, then the visit method will dispatch the call to the visit_BinOp method, and if the type of a node is Num, then the visit method will dispatch the call to the visit_Num method, and so on.

NodeVisitor 的 visit 方法非常通用,它根据传递给它的节点类型将调用分派给相应的方法。正如我之前提到的,为了使用它,我们的解释器继承了 NodeVisitor 类并实现了必要的方法。因此,如果传递给 visit 方法的节点类型是 BinOp,那么 visit 方法将调用 visit_BinOp 方法,如果节点类型是 Num,那么 visit 方法将调用 visit_Num 方法,依此类推。

Spend some time studying this approach (standard Python module ast uses the same mechanism for node traversal) as we will be extending our interpreter with many new visit_NodeType methods in the future.

花一些时间研究这种方法(标准的 Python 模块 AST 使用相同的机制进行节点遍历) ,因为我们将在未来使用许多新的 visit_Nodetype 方法扩展我们的解释器。

The generic_visit method is a fallback that raises an exception to indicate that it encountered a node that the implementation class has no corresponding visit_NodeType method for.

generic_visit 方法是一个fallback,它引发一个异常,以指示它遇到一个节点,但该节点的实现类没有对应的 visit_NodeType 方法。

Now, let’s manually build an AST for the expression 2 * 7 + 3 and pass it to our interpreter to see the visit method in action to evaluate the expression. Here is how you can do it from the Python shell:

现在,让我们为表达式2 * 7 + 3手动构建一个 AST,并将其传递给我们的解释器,以查看实际中的 visit 方法来计算表达式。下面是如何在 Python shell 中实现它的方法:

>>> from spi import Token, MUL, PLUS, INTEGER, Num, BinOp

>>>

>>> mul_token = Token(MUL, '*')

>>> plus_token = Token(PLUS, '+')

>>> mul_node = BinOp(

... left=Num(Token(INTEGER, 2)),

... op=mul_token,

... right=Num(Token(INTEGER, 7))

... )

>>> add_node = BinOp(

... left=mul_node,

... op=plus_token,

... right=Num(Token(INTEGER, 3))

... )

>>> from spi import Interpreter

>>> inter = Interpreter(None)

>>> inter.visit(add_node)

17

As you can see, I passed the root of the expression tree to the visit method and that triggered traversal of the tree by dispatching calls to the correct methods of the Interpreter class(visit_BinOp and visit_Num) and generating the result.

如您所见,我将表达式树的根传递给了 visit 方法,通过调用 Interpreter 类的正确方法(visit_BinOp 和 visit_Num)并生成结果,该方法触发了树的遍历。

Okay, here is the complete code of our new interpreter for your convenience:

好了,为了方便起见,下面是我们新解释器的完整代码:

""" SPI - Simple Pascal Interpreter """

###############################################################################

# #

# LEXER #

# #

###############################################################################

# Token types

#

# EOF (end-of-file) token is used to indicate that

# there is no more input left for lexical analysis

INTEGER, PLUS, MINUS, MUL, DIV, LPAREN, RPAREN, EOF = (

'INTEGER', 'PLUS', 'MINUS', 'MUL', 'DIV', '(', ')', 'EOF'

)

class Token(object):

def __init__(self, type, value):

self.type = type

self.value = value

def __str__(self):

"""String representation of the class instance.

Examples:

Token(INTEGER, 3)

Token(PLUS, '+')

Token(MUL, '*')

"""

return 'Token({type}, {value})'.format(

type=self.type,

value=repr(self.value)

)

def __repr__(self):

return self.__str__()

class Lexer(object):

def __init__(self, text):

# client string input, e.g. "4 + 2 * 3 - 6 / 2"

self.text = text

# self.pos is an index into self.text

self.pos = 0

self.current_char = self.text[self.pos]

def error(self):

raise Exception('Invalid character')

def advance(self):

"""Advance the `pos` pointer and set the `current_char` variable."""

self.pos += 1

if self.pos > len(self.text) - 1:

self.current_char = None # Indicates end of input

else:

self.current_char = self.text[self.pos]

def skip_whitespace(self):

while self.current_char is not None and self.current_char.isspace():

self.advance()

def integer(self):

"""Return a (multidigit) integer consumed from the input."""

result = ''

while self.current_char is not None and self.current_char.isdigit():

result += self.current_char

self.advance()

return int(result)

def get_next_token(self):

"""Lexical analyzer (also known as scanner or tokenizer)

This method is responsible for breaking a sentence

apart into tokens. One token at a time.

"""

while self.current_char is not None:

if self.current_char.isspace():

self.skip_whitespace()

continue

if self.current_char.isdigit():

return Token(INTEGER, self.integer())

if self.current_char == '+':

self.advance()

return Token(PLUS, '+')

if self.current_char == '-':

self.advance()

return Token(MINUS, '-')

if self.current_char == '*':

self.advance()

return Token(MUL, '*')

if self.current_char == '/':

self.advance()

return Token(DIV, '/')

if self.current_char == '(':

self.advance()

return Token(LPAREN, '(')

if self.current_char == ')':

self.advance()

return Token(RPAREN, ')')

self.error()

return Token(EOF, None)

###############################################################################

# #

# PARSER #

# #

###############################################################################

class AST(object):

pass

class BinOp(AST):

def __init__(self, left, op, right):

self.left = left

self.token = self.op = op

self.right = right

class Num(AST):

def __init__(self, token):

self.token = token

self.value = token.value

class Parser(object):

def __init__(self, lexer):

self.lexer = lexer

# set current token to the first token taken from the input

self.current_token = self.lexer.get_next_token()

def error(self):

raise Exception('Invalid syntax')

def eat(self, token_type):

# compare the current token type with the passed token

# type and if they match then "eat" the current token

# and assign the next token to the self.current_token,

# otherwise raise an exception.

if self.current_token.type == token_type:

self.current_token = self.lexer.get_next_token()

else:

self.error()

def factor(self):

"""factor : INTEGER | LPAREN expr RPAREN"""

token = self.current_token

if token.type == INTEGER:

self.eat(INTEGER)

return Num(token)

elif token.type == LPAREN:

self.eat(LPAREN)

node = self.expr()

self.eat(RPAREN)

return node

def term(self):

"""term : factor ((MUL | DIV) factor)*"""

node = self.factor()

while self.current_token.type in (MUL, DIV):

token = self.current_token

if token.type == MUL:

self.eat(MUL)

elif token.type == DIV:

self.eat(DIV)

node = BinOp(left=node, op=token, right=self.factor())

return node

def expr(self):

"""

expr : term ((PLUS | MINUS) term)*

term : factor ((MUL | DIV) factor)*

factor : INTEGER | LPAREN expr RPAREN

"""

node = self.term()

while self.current_token.type in (PLUS, MINUS):

token = self.current_token

if token.type == PLUS:

self.eat(PLUS)

elif token.type == MINUS:

self.eat(MINUS)

node = BinOp(left=node, op=token, right=self.term())

return node

def parse(self):

return self.expr()

###############################################################################

# #

# INTERPRETER #

# #

###############################################################################

class NodeVisitor(object):

def visit(self, node):

method_name = 'visit_' + type(node).__name__

visitor = getattr(self, method_name, self.generic_visit)

return visitor(node)

def generic_visit(self, node):

raise Exception('No visit_{} method'.format(type(node).__name__))

class Interpreter(NodeVisitor):

def __init__(self, parser):

self.parser = parser

def visit_BinOp(self, node):

if node.op.type == PLUS:

return self.visit(node.left) + self.visit(node.right)

elif node.op.type == MINUS:

return self.visit(node.left) - self.visit(node.right)

elif node.op.type == MUL:

return self.visit(node.left) * self.visit(node.right)

elif node.op.type == DIV:

return self.visit(node.left) // self.visit(node.right)

def visit_Num(self, node):

return node.value

def interpret(self):

tree = self.parser.parse()

return self.visit(tree)

def main():

while True:

try:

text = input('spi> ')

except EOFError:

break

if not text:

continue

lexer = Lexer(text)

parser = Parser(lexer)

interpreter = Interpreter(parser)

result = interpreter.interpret()

print(result)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Save the above code into the spi.py file or download it directly from GitHub. Try it out and see for yourself that your new tree-based interpreter properly evaluates arithmetic expressions.

将上面的代码保存到 spi.py 文件中,或者直接从 GitHub 下载。试一试,看看你的新的基于树的解释器能否正确地计算算术表达式。

Here is a sample session:

下面是一个例子:

$ python spi.py

spi> 7 + 3 * (10 / (12 / (3 + 1) - 1))

22

spi> 7 + 3 * (10 / (12 / (3 + 1) - 1)) / (2 + 3) - 5 - 3 + (8)

10

spi> 7 + (((3 + 2)))

12

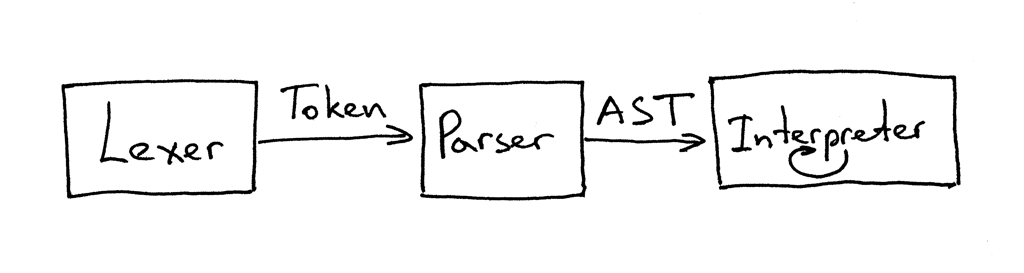

Today you’ve learned about parse trees, ASTs, how to construct ASTs and how to traverse them to interpret the input represented by those ASTs. You’ve also modified the parser and the interpreter and split them apart. The current interface between the lexer, parser, and the interpreter now looks like this:

今天,你已经学习了解析树、 ASTs、如何构造 ASTs 以及如何遍历它们以解释这些 ASTs 所表示的输入。你还修改了解析器和解释器,并将它们拆分开来。现在 lexer、 parser 和解释器之间的接口如下所示:

You can read that as “The parser gets tokens from the lexer and then returns the generated AST for the interpreter to traverse and interpret the input.”

你可以将其理解为“parser从 lexer 获取token,然后返回生成的 AST,以便解释器遍历和解释输入”。

That’s it for today, but before wrapping up I’d like to talk briefly about recursive-descent parsers, namely just give them a definition because I promised last time to talk about them in more detail. So here you go: a recursive-descent parser is a top-down parser that uses a set of recursive procedures to process the input. Top-down reflects the fact that the parser begins by constructing the top node of the parse tree and then gradually constructs lower nodes.

今天就到这里,但是在结束之前,我想简要地谈谈递归下降解析器,也就是给它们一个定义,因为我上次承诺要更详细地讨论它们。因此,你可以这样做:递归下降解析器是一个自顶向下的解析器,它使用一组递归过程来处理输入。自顶向下反映了这样一个事实,即解析器从构造解析树的顶部节点开始,然后逐渐构造较低的节点。

And now it’s time for exercises 😃

现在是练习的时间了:)

- Write a translator (hint: node visitor) that takes as input an arithmetic expression and prints it out in postfix notation, also known as Reverse Polish Notation (RPN). For example, if the input to the translator is the expression (5 + 3) * 12 / 3 than the output should be 5 3 + 12 * 3 /. See the answer here but try to solve it first on your own.

- 编写一个转换器(提示:节点访问器),将算术表达式作为输入,并以后缀表示法输出,也称为反向波兰表示法(RPN)。例如,如果输入到转换器的表达式是(5 + 3)* 12 / 3,那么输出就应该是5 3 + 12 * 3 /。在这里看到答案,但试着先自己解决它。

- Write a translator (node visitor) that takes as input an arithmetic expression and prints it out in LISP style notation, that is 2 + 3 would become (+ 2 3) and (2 + 3 * 5) would become (+ 2 (* 3 5)). You can find the answer here but again try to solve it first before looking at the provided solution.

- 编写一个转换器(节点访问者),它接受一个算术表达式作为输入,并以LISP风格的表示法输出它,即2 + 3将变成(+ 2,3),(2 + 3 * 5)将变成(+ 2(* 3 5))。你可以在这里找到答案,但还是试着先解决它,然后再看提供的解决方案。

In the next article, we’ll add assignment and unary operators to our growing Pascal interpreter. Until then, have fun and see you soon.

在下一篇文章中,我们将为不断增长的 Pascal 解释器添加赋值和一元运算符。在那之前,玩得开心点,很快就能见到你。

P.S. I’ve also provided a Rust implementation of the interpreter that you can find on GitHub. This is a way for me to learn Rust so keep in mind that the code might not be “idiomatic” yet. Comments and suggestions as to how to make the code better are always welcome.

另外,我还提供了一个在 GitHub 上可以找到的解释器的 Rust 实现。这是我学习 Rust 的一种方法,所以请记住,代码可能还不是“惯用的”。关于如何使代码更好的评论和建议总是受欢迎的。

Here is a list of books I recommend that will help you in your study of interpreters and compilers:

下面是我推荐的一些书籍,它们可以帮助你学习解释器和编译器:

- Language Implementation Patterns: Create Your Own Domain-Specific and General Programming Languages (Pragmatic Programmers)

语言实现模式: 创建您自己的特定领域和通用编程语言(实用程序员) - Writing Compilers and Interpreters: A Software Engineering Approach

编写编译器和解释器: 一种软件工程方法 - Modern Compiler Implementation in Java

现代编译器在 Java 中的实现 - Modern Compiler Design

现代编译器设计 - Compilers: Principles, Techniques, and Tools (2nd Edition)

编译器: 原理、技术和工具(第二版)

All articles in this series:

本系列的所有文章:

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 1. 让我们构建一个简单的解释器

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 2. 让我们构建一个简单的解释器

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 3. 让我们构建一个简单的解释器

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 4. 让我们构建一个简单的解释器

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 5. 让我们构建一个简单的解释器

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 6. 让我们构建一个简单的解释器

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 7: Abstract Syntax Trees 让我们构建一个简单的解释器。第7部分: 抽象语法树

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 8. 让我们构建一个简单的解释器

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 9. 让我们构建一个简单的解释器

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 10. 让我们构建一个简单的解释器

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 11. 让我们构建一个简单的解释器

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 12. 让我们构建一个简单的解释器

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 13: Semantic Analysis 让我们建立一个简单的解释器。第13部分: 语义分析

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 14: Nested Scopes and a Source-to-Source Compiler 让我们构建一个简单的解释器。第14部分: 嵌套作用域和源到源编译器

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 15. 让我们构建一个简单的解释器。第15部分

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 16: Recognizing Procedure Calls 让我们建立一个简单的解释器。第16部分: 识别过程调用

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 17: Call Stack and Activation Records 让我们构建一个简单的解释器。第17部分: 调用堆栈和激活记录

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 18: Executing Procedure Calls 让我们构建一个简单的解释器。第18部分: 执行过程调用

- Let's Build A Simple Interpreter. Part 19: Nested Procedure Calls 让我们构建一个简单的解释器。第19部分: 嵌套过程调用